Throughout the world, cooperatives are engaging people in prison and individuals who have been released from the carceral system to create dignified work that benefits the individual and the broader community.

Can cooperatives, based on the values of democracy, equity, and “one person, one vote,” offer sustainable solutions for people navigating reentry in the United States? Collective REMAKE, a hybrid cooperative nonprofit in Los Angeles County, is working to do just that, along with a broad stakeholder network.

Los Angeles County runs the largest jail system in the world, with the capacity to cage over 20,000 individuals. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the average population in the county jail facilities was around 17,000 people. Because of the virus’s rapid spread through those facilities, nearly 5,000 individuals were released early or pre-trial; despite that, the jail population is now creeping back up. Black people make up approximately eight percent of the Los Angeles County population, yet they are 29 percent of the jail population.

Thousands of people are released from prison and jail every month to Los Angeles County. Most plan to stay at home, plan to support loved ones, plan to give back. Yet the odds are stacked against them. Upon release, and often on parole, individuals return home to areas that have been disenfranchised politically, socially, and economically over the last 40–50 years.

The last four decades have been a period of extreme economic division caused by an unbridled inequitable market, bolstered by measures put forth by conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats alike. Neoliberal policies have created what Steven Pitts calls the Age of Inequality. In the same timeframe, 1980 to present, a similar line on the graph represents the drastic increase in incarceration rates, rises in higher education fees, slashes in funding for social programs and K-12 education, flight of industry, and loss of living wage jobs.

The extraction of people and wealth has traumatized low-income communities and communities of color. In Los Angeles, where I live, the racial disparities have been especially egregious. Some call it “Apartheid L.A.”

The impacts of this apartheid have been exposed and compounded during the pandemic. In June 2020, the unemployment rate in predominantly Black neighborhoods in Los Angeles was 22–32 percent, whereas in white areas it was between 10 and 17 percent. For people who have a criminal conviction in their past, opportunities to find work for a sustainable wage are scarce. Racism in the job market is as prevalent as ever, even for those without a record.

Worker-owned businesses and other kinds of cooperatives can ignite a local economy in communities that have been economically disenfranchised and suffer from over-policing and high rates of incarceration. Cooperatives offer a democratic business structure and embedded community, a viable opportunity for individuals who are otherwise discriminated against in the job market because they have a criminal record.

As Thomas Porter-Smith, a board member with lived experience in the California prison system, explains, “Cooperatives offer an accepting environment, where people just getting out can get grounded, build a social network, and at the same time, learn to stand on their own two feet; and they are able to work for the benefit of their loved ones and their community.”

Although cooperatives of all kinds are around us, many people in the US would be at a loss if asked to describe what a cooperative is. In the US, nonprofit circles and the growing world of social enterprise do not embrace the notion of cooperative values and principles as they do in Europe and elsewhere. As defined by the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA), “A cooperative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise.”

Seven cooperative principles, along with a set of values, were adopted by the ICA in 1995. The original principles were developed in the 1840s by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers—a group of intellectuals, artists, and weavers in Manchester, England—who broke from the exploitive textile industry, and from shops where mill owners often mixed their flour with sawdust to increase profits—to create cooperative businesses. Their first business was a small shop owned by 28 people that sold butter, flour, oatmeal, and sugar. To become an owner, members paid one pound sterling, a sizable sum in those days. Many, however, paid in installments of two pence a week. (Back in the 1840s, there were 240 pence to a pound, so buying an ownership share required 120 weeks of payments at that rate.)

The Rochdale Pioneers were radical for the times, comprising people from different social classes and with diverse religious beliefs. The first woman became a member in 1846, just 16 months after the cooperative’s founding. Women had equal voting rights to men—a big deal in 1846—but were outnumbered due to the fact that fewer women had access to money than men.

The set of seven principles under which cooperatives operate today are:

- voluntary and open membership

- democratic member control

- member economic participation

- autonomy and independence

- education training and information

- cooperation among cooperatives

- concern for community

As the ICA says, co-ops embrace the values of democracy, equity, equality, self-help, self-responsibility and solidarity; they promise honesty, openness, community engagement, and caring for others.

Of course, as Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and others remind us, the history of cooperatives does not just stem from these Rochdale pioneers. As Dr. Gordon Nembhard—author of Collective Courage, a history of Black cooperatives in the US— wrote in NPQ this fall, there is a “long history of economic cooperation among all peoples, especially early African societies and First Nations.” For example, savings and credit arrangements have long been prevalent among people of African descent and are precursors to credit exchanges and credit unions.

In Los Angeles, at Collective REMAKE, our mission is to build worker-owned businesses and other kinds of cooperatives with people who have returned home from prison or jail and are navigating reentry. Also welcome are their loved ones and family members, as well as others who are pushed to the margins of the economy.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

We use cooperative principles and values as a guide as we operationalize democratic practices. Our organization is a nonprofit with a democratic structure encapsulated in our bylaws. The board represents the communities we work with; no less than 50 percent of the voting members will be people who are directly impacted by incarceration.

Our hybrid model was designed with a circular structure that administers practical ways to integrate an active stakeholder network needed to support education programs and co-operative development. The democratic framework was inspired by El Centro Cultural de México in nearby Santa Ana, a collective supporting the development of cooperatives with Immigrant populations.

The Santa Ana collective houses a number of projects in cuadros (hubs), and they partner with several community organizations. All members take part in consensus decision-making processes. The formation of the Santa Ana collective was informed by a Zapatista organizing model, in which a representative from each community participates in the central decision-making body of the broader organization.

Our own future vision includes hubs made up of diverse community partners. Designated hubs include administration, business and finance, cooperative design, legal, marketing, and wellness. Each hub will have representation in a central decision-making body that will support organizational growth and direction. The developing cooperatives inspired through the cooperative education and development workshops will be supported by the broader network, and they will also have democratic representation.

There is a new wave of cooperative efforts around the country and in Los Angeles. The future work of our collective, and its potential for growth, is dependent on a growing network of stakeholders who support our mission.

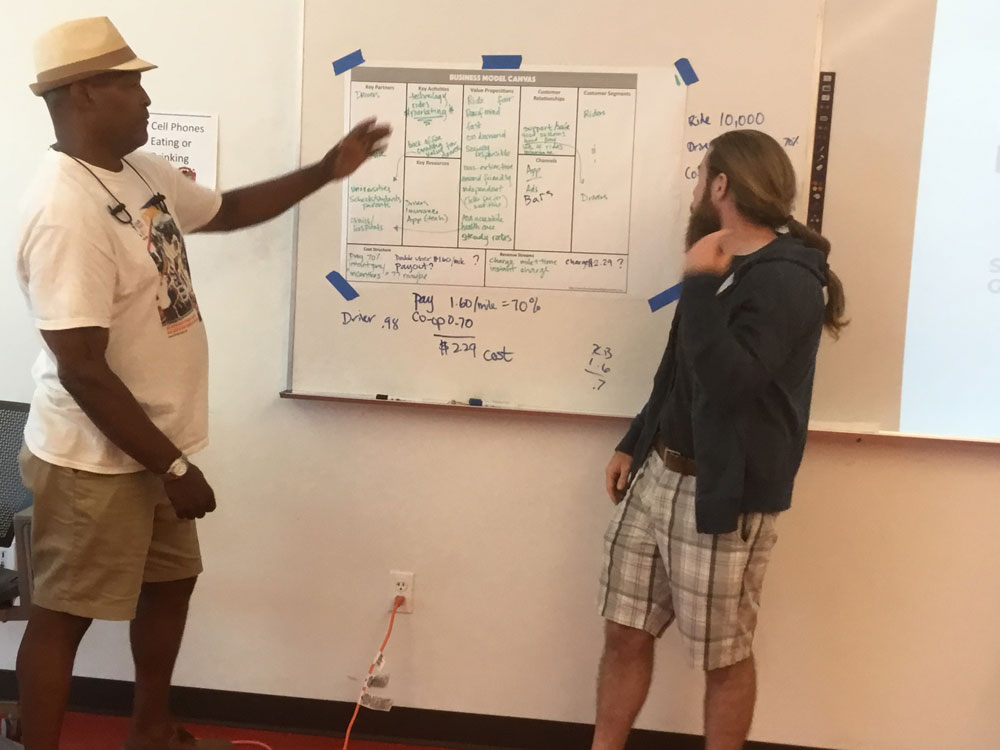

Since 2016, we have conducted cooperative education and development workshops and seminars at diverse locations in South Los Angeles. In participatory meetings with board members and partners, we have developed a series of workshops, including Introduction to Cooperatives: The Principles and Values; History of Cooperatives Around the World, A Just Transition—Moving from an Extractive Economy to a Caring Economy, Practicing Democracy, Envision Your Co-op Through the Business Model Canvas, Elements of a Business Plan, Introductory Legal Considerations When Starting a Co-op, Finances and Start-Up Budgets, and Introduction to Time Banking. We continue to design new modules to address participatory democracy, sustainability, financial wellness, and personal health.

Dozens of community partners and visiting cooperatives have supported the workshops with content, presentations, meeting space, food donations, and outreach. Others provide legal, financial, and strategic consultation. It is not possible to name everyone in our stakeholder network. However, key players who have been laying the groundwork for years and are still building the vision include the Los Angeles Union Cooperative Initiative (LUCI) and the L.A. Eco Village. More recently, L.A. Co-op Lab has been supporting innovative development services for a spectrum of new co-operative businesses.

Alongside implementing cooperative education and development programming, Collective REMAKE seeks to develop participatory democratic practices internally and with our broader stakeholder network. As modeled by former co-op practitioners and philosophers, we are developing education programs that support people to find their own agency, understand the value of their individual and collective assets, and build sustainable economic solutions according to the needs of their community.

We began by prioritizing the development of education programming in line with the teachings of co-op philosophers and actors. Our sources of inspiration have included: Father José María Arizmendarrieta (also known as Arizmendi), a founder of the Mondragón cooperatives in Spain, a network of 96 worker co-op businesses that employ over 81,000 people; Father Jimmy Tompkins and Father Moses Coady, founders of the Coady International Institute at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia; and Father A. J. McKnight and Carol Prejean Zippert, co-founders of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in Lafayette, Louisiana.

In each case, these founders started local cooperative development through adult education programs. Cooperative theory proposes that through education, everyone has some level of capacity to analyze problems, identify assets, and develop solutions.

Cooperative philosophy is also in step with the teachings of Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, in which he famously wrote, “For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.”

At the time that COVID-19 hit, our collective was running our Cooperative Education and Development Workshop series at two locations. Over 30 individuals, the majority of whom were returning citizens—men, women, and nonbinary LGBTQ folks—were engaged midway through a series of ten workshops. As the COVID-19 crisis became a reality, we immediately adjusted our budget, purchased laptops, and safely delivered them to participants’ homes. We worked with workshop participants one-on-one so that they could continue to access Cooperative Education and Development Workshops online.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, we continue to implement workshop series online. We recently initiated a train-the-trainers program; participants have the opportunity to become facilitators and future members. We are also moving forward with an advanced co-op development program.

In a recent webinar, An Introduction to Co-operatives, my colleague LaRae Cantley stated:

I grew up in South L.A. in the eighties, and I was exposed to a lot of the pain and historical disparities faced by people of color, all due to systemic and institutional racism. I survived childhood trauma, domestic abuse, homelessness, and the impacts of the criminal injustice system. I have experienced first-hand the challenges to secure economic stability. In 2017, I began my journey through the cooperative education and development series, where I gained new hope for opportunities to create a sustainable income and become a business owner—and do it in a way that is collaborative, not in a way that is competitive, working with like-minded people who have faced similar hardships and structural barriers like myself. We have learned about the history, values, principles and benefits of co-operatives; they offer an opportunity to build economic independence while caring for the community. Today, with the support of Collective REMAKE, I am working with two partners to design a consulting cooperative.

Now is the time, like no other, to build networks of cooperative businesses. Together, we can generate dignified work, create purpose and value, and draw extracted wealth back to communities that have been hit the hardest by neoliberal economics and centuries of systematic oppression.